If you’re a design leader, you can’t make assumptions and expect to reach your goals.

When we have a Purpose and set goals for ourselves (like hiking to the top of a mountain), we identify our objective (the Peak), then determine the best way (the Path) to reach that goal and how we’ll carry out that Plan (the tactics).

Every UX strategy needs a solid framework to get started and stay on track. Sticking with the metaphor of a climb, let’s look at the 5 core elements of strategic frameworks.

1. Purpose – Why am I climbing this thing in the first place?

Is the goal clearly stated and understood? Has it been validated as something worthwhile to pursue? For whom? Does the team working toward this goal understand its purpose?

2. Peak – Choose your destination—or at least aim in a general direction. You may sometimes hear of companies focusing on their “North.”

3. Path – How you get to the peak matters.

How you climb the mountain matters. The path needs to help the organization not just meet financial targets, but also mature the organization in the process.

4. Point – Opportunity to pause, analyze, and measure.

Points on the path aren’t merely deliverables or activities. They should regularly confirm and/or adjust your goals and the path toward that goal.

5. Plan – Every expedition needs a plan for tactics.

I need the right training & equipment. I may need other people (Who should I bring versus station remotely?). Do I need to let others know where I’m going?

A lot of people mistake the Path for the Plan. True, each activity is a step toward the goal, but tactics are only one part of the strategy. The path is not a collection of tactics.

Constantly re-evaluate your framework to keep your strategy on track.

Step 1: Purpose and Peak

Purpose ties into your vision of the intended outcome. It’s the first thing you define. I always start there.

Defining purpose means asking questions like:

- Why are we here?

- What value will we create?

- Who benefits from this value?

- Why will they care?

The Peak or vision (your intended outcome/destination) clarifies your purpose:

- Communicate the pain felt if the purpose is not achieved.

- Demonstrate one way the problem(s) get solved.

- Show how the problem’s solution adds value to users.

- Propose a realistic means of achieving the solution.

- Clarify any data that supports the purpose.

To make any peak truly valuable, it needs emotional and tangible merit. It can’t be expressed as a collection of features. Features only list the ingredients in your recipe – they don’t convey the whole experience.

Here’s an example from an initiative I led at Rackspace.

To define the purpose and peak, I dug into what “Managed Cloud” actually meant. I gathered a cross- functional group of people together for 2 days. First, we dove into “What is ‘managed’?” We deconstructed the term to identify the value for our customers.

I had to break through a lot of jargon bear traps—you know, the ones that leave you saying, “But that isn’t what ‘managed’ means. You’re making up random meanings.” Reflect people’s definitions back to them so that they gain a better understanding.

I then led the team through a storytelling exercise, where each person created a story with a customer (a Rackspace employee) and a scenario that reflected the new value. People didn’t simply tell fanciful stories. They explained what was wrong today and how we might improve that situation. By seeing the negative stories against a brighter future, our Purpose became more relevant and approachable.

We then captured that story in a shareable artifact that could discuss with other departments. In this case, we created a short photo essay with voice narration. A simple vision prototype.

We played the video in front of internal and external stakeholders and got a tremendous amount of positive feedback about what was working and what wasn’t. Once we connected user research to the points made in the video, buy-in soared. Product design, product management, and engineering all started prioritizing backlog items based on our new Purpose and Peak.

Step 2: Charting Your Path

The Path you choose to reach your destination isn’t the only feasible route. Each possibility requires weighing a variety of factors before adjusting course. Don’t decide your Path by thinking the “end justifies the means.”

Weighing the Options

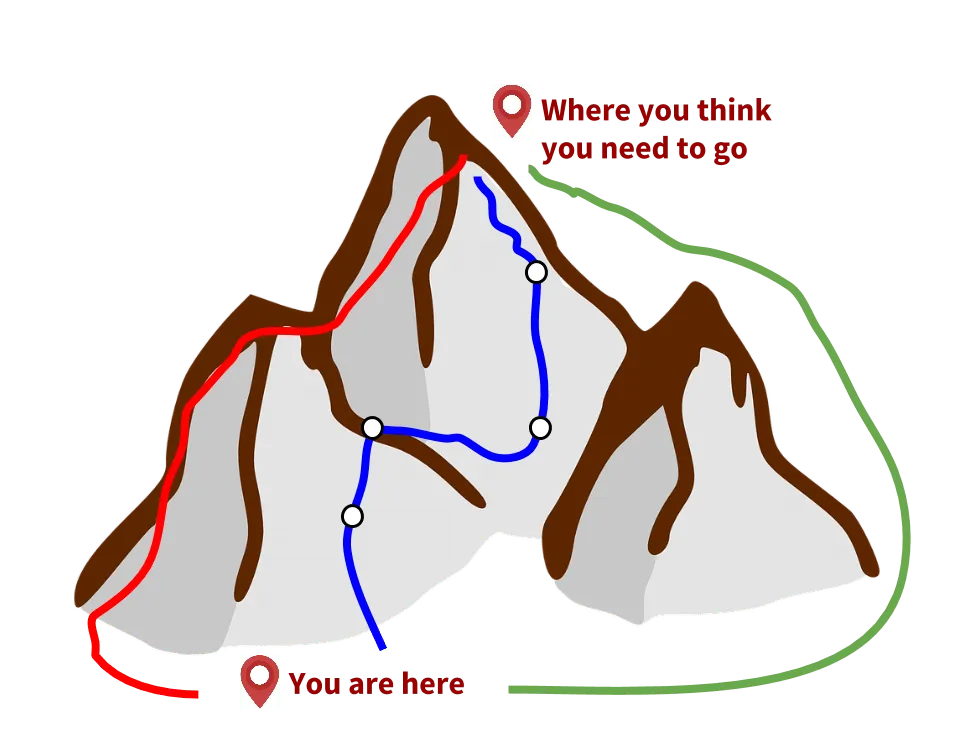

Let’s look at our mountain again:

Let’s say the red line has the following properties:

- Cheap.

- Fast.

- Quality (whatever that means to the organization).

Sounds like a good option. But is it? What if we throw in some factors that may or may not work for you?

- Requires reassigning key players from other projects (of lower priority, of course).

- Creates technical debt without a plan for paying it back.

- Doesn’t account for team development (to be ready for the next thing).

- The product releases on time, but lacks coordination with parallel sales & support efforts.

- Fewer points in the process to validate assumptions or apply lessons learned.

- No ability to instrument deliverables and offerings.

Does the red path still look appealing? What other options (and factors) can we consider?

If we go with the blue line, the path looks like this:

- A bit more expensive (short term).

- Takes longer to get to market—but more confidence that we deliver value.

- Results in better quality than we’d otherwise get—which leads to surpassing customer-based KPIs (like NPS changes).

- Provides definite answers to the bullet points associated with the red trail.

By taking the blue trail, you ship in a way that delivers the greatest value for both you and your customers.

Choosing the Right Path

How do you find the right path?

Know your organization’s culture, business, competition, capabilities, etc. Simple SWOT analysis helps, as well as the resourcing matrix explained in the previous chapter. Another tool I find tremendously useful is the“Culture Map,” as popularized by XPLANE. In this canvas, you uncover how the more intangible aspects of culture impact outcomes.

As you evaluate your options, consider the following criteria:

- How much technical and UX debt are we creating? Is it acceptable given our current state? How do we plan to pay it off?

- What other projects need to be deprioritized to accommodate our path? What will that cost the organization?

- How much time are we afforded to validate our assumptions periodically?

- Are we allowing enough time and leeway for non-design stakeholders to understand decisions (or weigh in with their own)?

Step 3: Creating Evaluation Point(s)

Back in the days before GPS, we followed directions to get around, and the quality varied greatly depending on the person, their navigation skills, and their familiarity with the area.

At some point, you need to confirm you’re on course. Re-evaluate successes and failures, not to mention refine your target Peak.

We follow a cognitive process called “OODA”: Observe, Orient, Decide, Act. OODA (I pronounce it “OO-dah”) takes place at a stopping point to allow for:

- Data collection

- Analysis of that data

- Reflection on the analysis

- Synthesis of a set of hypotheses

- Evaluation of hypothesis value

- Amendment to the existing plan based on new insights

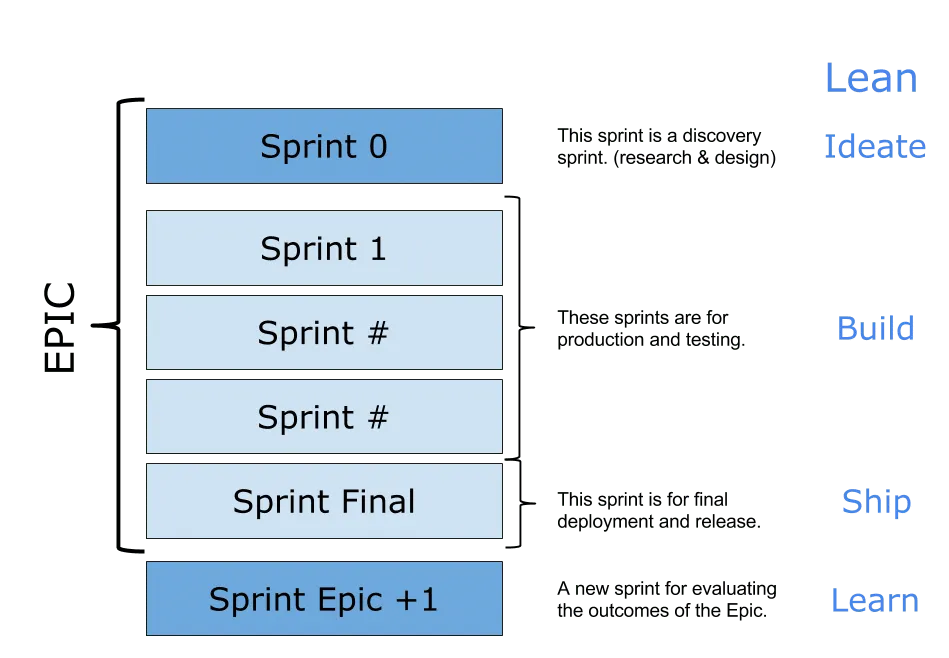

In an Agile process, let’s say that each segment of your path is the equivalent of an epic. Your strategic stopping point is then the “Sprint Epic +1” (shown below).

Just like how we use the “Sprint 0” for UX research and discovery, we schedule a “sprint epic +1” to reflect on the past epic based on agreed upon metrics. Beyond a basic post-mortem or retro, we dedicate a full sprint length for analysts, designers, and product team members to dive deep into each success and mistake – then adjust the path accordingly.

We review the whole epic because the tight timing of a sprint might hide deeper insights around the overall vision. The extra time is a worthwhile investment in giving everyone a larger perspective beyond features.

Step 4: Plan to Validate Assumptions

Your success at the Points in your path is 100% affected by how well you Plan.

The best way to create a plan is to work backwards to answer the question, “What do I need to achieve this?”

Start by creating post-its for the beginning and the end, sticking them to the biggest wall you can find. This methodology is called “back planning.” You start with your intended outcome, then keep evaluating backward until you reach the point where you know you’ll have what you need to start.

Below, I’ll explain how I might complete this exercise in an enterprise setting for an IT ticketing system.

The final outcome

Help customer IT managers better communicate with our IT operators across multiple channels. The new system isn’t just for messaging, but incorporates workflow management that reacts to decision making, and allows end-users to customize governance. Our goal is increasing NPS scores by 10 points.

Our current state

Currently, we only offer email notifications with no contextual information. The notifications don’t always target the right person on the customer’s team.

Our IT operators send notifications with a basic ticketing system:

- Little customization

- Only works on a desktop browser

- Can only send in bulk to one person. The IT manager recipient then needs to resend to people on their team.

Our rough plan

Now that we know the beginning and end, we start filling in the gaps between. You can work backwards or forwards (I prefer working backwards).

In this case, working backwards, I first deconstruct both the experience and functionality of the end point as best I can:

- We need a mobile application that scales to tablet.

- If we have one already, what can/can’t it do that maps against the end point?

- I’ll need to research what platforms my customers are using, but will probably have to use the top two major platforms.

- We need to create or buy a business process management engine.

- We’ll need to create scenarios of governance, co-designing these with our customers.

- Once we understand the scenarios we can map against build or buy scenarios.

- A notification engine based on a new monitoring stack will be needed.

- Trend analysis to aid in predictions

- Graphics engine to better add visual context to notifications (build or buy question to discuss with development and product management)

- Our IT operators need a compatible console of their own to work with the new notification system.

- Does the existing system have the necessary APIs to work with the new business process management engine?

While these ideas might change once you start designing and testing, you at least create a plan for stakeholder discussion.

You start creating a backlog. “Based on where we are today, what do I need to start working on this backlog item?” You just keep repeating these steps until the dots connect into a series of loosely defined epics and sprints.

During this planning, you’ll also reveal questions not directly related to the product. These questions relate to other strategic considerations around team building, culture, customer management, etc.

For example, if no existing team was familiar with mobile development or responsive design systems, you now need to also start planning for training or recruiting to fulfill that competency. Another example is aligning sales, support, and delivery teams so that they receive training materials to understand the new customer experience.

And of course, lastly, you need to also write in your research needs for generating ideas and validating design concepts.

Conclusion

Strategy is “intent with purpose.”

Organizations like IBM, GE, Honeywell, Intuit, CapitalOne, USAA, and many others have all dedicated tremendous resources toward design as an organizational and executive competency.

As design teams grow in large organizations, so too does the demand for good design leaders. To stay competitive today, design leaders can’t just be masters of process. They need to craft a digestible vision that aligns with the bottom line, vet it against customers and stakeholders, and create a clear plan for fulfilment.

Use your tools of story and visual artifacts to bring visions to life. Develop your team to build (and even challenge) that vision. And always remember to communicate how everything connects with the greater goals of the business.

For more advice, download the free Guide to UX Leadership by Dave Malouf.