Lean ensures we’re building the right product and Agile helps ensure we build the product right.

As the blog post Lean vs. Agile UX explains, Lean focuses more on product strategy while Agile focuses on product design processes.

In this post, I’ll explain UX design principles inspired by processes from both Lean and Agile UX.

First, a Super Brief History of Agile

First coined in 2001 by 17 well-known developers in the Manifesto for Agile Software Development, Agile originally referred to a software development process that was flexible and collaborative. Teams focused on creating working software through continuous customer validation rather than focusing solely on technical requirements.

Photo credit: Four Worlds. Creative Commons.

Specifically, Agile seeks to fulfill 12 principles:

-

- Customer satisfaction

-

- Harnessing change

-

- Faster development timelines

-

- Collaboration

-

- Building projects around motivated individuals

-

- Face-to-face communication

-

- Working software as the key benchmark for success

-

- Sustainable development

-

- Technical excellence

-

- Simplicity

-

- Self-organizing teams

- Self-reflecting teams

If these principles just sound like the basis of a lot of good contemporary design work, that’s no accident.

Jim Highsmith, one of the original authors of the Manifesto, even said recently in his preface for the book Agile Experience Design: A Digital Designer’s Guide to Agile, Lean, and Continuous:

“Specialisation wasn’t the primary problem—collaboration was. As the Agile movement matured, we’ve added back specialists as we’ve learned to integrate them into Agile teams. That’s not to say that having a more general set of skills isn’t very valuable, but in our complex world there is still a need for expertise.”

As we design more complex products like social media products and subscription-based services, our teams and processes are only going to grow.

So while Agile has undoubtedly made a major impact on the design world, it might be time to update to reflect the realistic demands of current UX projects.

UX Is An Attitude, Not Just A Skillset

I’m always hesitant to describe to clients and fellow researchers a hard-and-fast list of skill sets that all UX developers should be versed in.

Unlike sister disciplines like web development, UX is a much broader discipline with more intangible skills. UX is more of an attitude than just a skillset.

UX designers are responsible for ensuring a high-quality user experience for a product or service. However, how they do so changes from project to project.

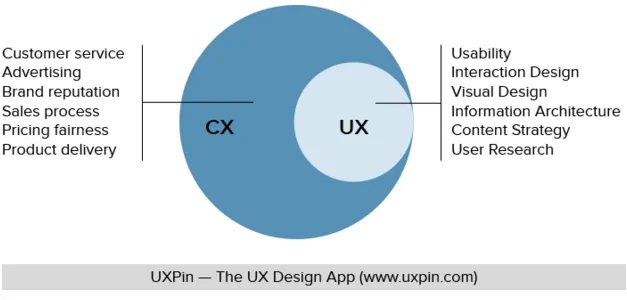

Photo Credit: Kissmetrics

Consider these two examples from some of my recent projects as a UX consultant:

Project A: A client needed a content audit of their recently launched website. They were concerned the website structure wasn’t optimized for their target users.

Project B: A grant-funded web application developed through a university wanted a UX strategy for growing their application beyond its initial prototype.

Though I used my expertise in UX and Agile to advise both of these clients, each client had very different needs.

Project A required a quick, lean audit with immediately-actionable feedback. Project B had a much longer timeline that much more closely resembled a waterfall approach, even though the project was being developed in a relatively lean, collaborative environment (two individuals besides myself doing most of the development work).

In fact, I would hazard to say that if I had tried to advise both of these clients in the exact same way, one of these projects would have failed. Had I tried to get Project A to more closely resemble a collaborative, Agile approach, the client would’ve gone somewhere else for help with their problem.

Had I tried to get Project B to more closely resemble a lean approach with tight timelines, the clients would’ve seen me as too pushy and sensitive to the limitations of their organization.

The bottom line is that a one-size fits all UX design process just doesn’t work. You have to take it on a case-by-case, situation-by-situation basis.

And Now the 12 Agile UX Principles

Rather than redefining the Agile wheel, we should focus on moving toward principles that weigh the various costs and benefits of Agile principles given the project directly in front of us. That’s really what we do as UX professionals, after all.

We know the “best practice,” and we need to apply that best practice to the situation in front of us.

Here’s the 12 principles of Agile UX based on my experience in real projects:

1. Customer experience (CX): We don’t just want customers to be “satisfied.” We want to design user experiences that are cognizant of both business realities and customer contexts. Customers are not always users, but most customers are going to use one or more points of contact for a given organization.

Photo credit: UXPin

2. Harnessing technological and social change: We need to define changes that we expect in the next iteration of a project, rather than just adapting to current changes. Instead of putting out fires, our job as UX professionals should be to create future-ready designs that help clients adapt to new challenges.

3. Development timelines that make good use of resources: Fast is a relative term. For some organizations, getting everyone in the same room once a month can be a huge improvement. Here’s where Lean is important: we should always strive as UX professionals to make efficient use of resources without short-changing our clients by focusing on process improvement, not on process perfection.

4. Adaptive collaboration:The degree of collaboration changes from project to project. Some problems clearly fall within the purview of a particular specialist, some will require an entire team to solve, and some require sub-groups of a team. Some clients can solve problems on their own and some require more hands-on guidance.

5. Building projects around motivated individuals: Organizational and technological constraints always matter. We can’t advise organizations to put all their investments into bleeding-edge solutions if they don’t have the capacity to recover if these solutions fail. We should encourage change, but always track ROI.

6. Effective communication across team channels: Rather than mandating one form of communication, strive to build more coordinated communication across individuals within teams. This would be more of a tactical, cross-functional approach to communication, rather than mandating everyone be in the same room for every project. Tools promoting collaborative design like Slack and UXPin help consolidate documentation and feedback in one place.

7. Working applications and high-quality UX as success benchmarks: Your application can make a million decisions for users at the first keystroke or gesture, but if users don’t see that value, your product will mostly likely fall flat. At the same time, the most bleeding-edge technology is useless if proof-of-concept isn’t achieved early through lo-fi prototyping.

8. Sustainable development: This goes back to principle 3. Some features within a specific application will probably become obsolete in future versions. New features are also the lifeblood of successful product launches. Product iterations should always be a balancing act between what existing customers expect and what new customers need.

9. Technical excellence is relative: In some organizations, like institutions of higher education or non-profits, for example, the most viable solutions might be considered obsolete in other venues. And that’s OK because we must consider price-point and organizational capacity. A small non-profit has very different technical requirements than a multinational corporation.

10. Simplicity: Again, it depends. The simplest solution isn’t always the best one, especially if that solution neglects user, organizational, or technical realities.

11. Cross-functional teams: UX specialization is nothing to be feared. Silos are the real problem. When specialists don’t talk to one another, we get products that neglect one or more elements. As long as productive, cross-channel communication is happening within organizations, then specialization is okay.

12. Adaptable, flexible teams: Self-reflection is great, but can teams adapt to new challenges? Can they roll with the punches? Are they comfortable with discomfort? We need project teams who are hungry to learn what users want and what technologies require. Great design teams are great improvisers.

These 12 principles are a starting point to help you succeed with any UX project.

However, as I’ve said before, the application of these principles are case-by-case, situation-by-situation. You may apply all 12 or you may employ only a few.

When it comes to UX, there is never a one-size fits all solution or approach. Triangulate the user, business, and technical constraints, then adapt your process accordingly.

Don’t underestimate your instincts.

For more advice, download the free Agile UX e-book bundle. You’ll get 200+ pages of advice by designers from PwC, Slack, Autodesk, and others. Learn best practices based on real-life Agile UX processes.